Challenging

‘If the children of company directors and MPs and disc jockeys died horribly of sickle cell anaemia, it would be a more popular cause than polio and cystic fibrosis research funds put together, and Black people themselves would at least be aware of the risks they face.’

Gerry Dawson, ‘Sickle Cell Anaemia: The Black Killer’, Race Today (September 1974)

For decades, services for people with sickle cell trait and disease were underdeveloped or nonexistent across the United Kingdom. People with sickle cell disease often experienced racism in their encounters with the National Health Service and the British state. Multiple voluntary organisations emerged in the 1970s and 1980s, to champion the cause of sickle cell and challenge the racism and stigma that affected its treatment. By the 1990s, sickle cell had become a highly politicized issue. After decades of campaigning, the National Screening Programme for Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia newborns began in 2005, and clinical standards for sickle cell treatment were adopted by the NHS for the first time in 2008.

Volunteers at work in the Sickle Cell Society, c.1983

Footballers Garth Crooks and Chris Hughton with a young woman with sickle cell disease at Central Middlesex Hospital in 1985. Copyright Garth Crooks.

Some founding members of the Sickle Cell Society, pictured in 1979

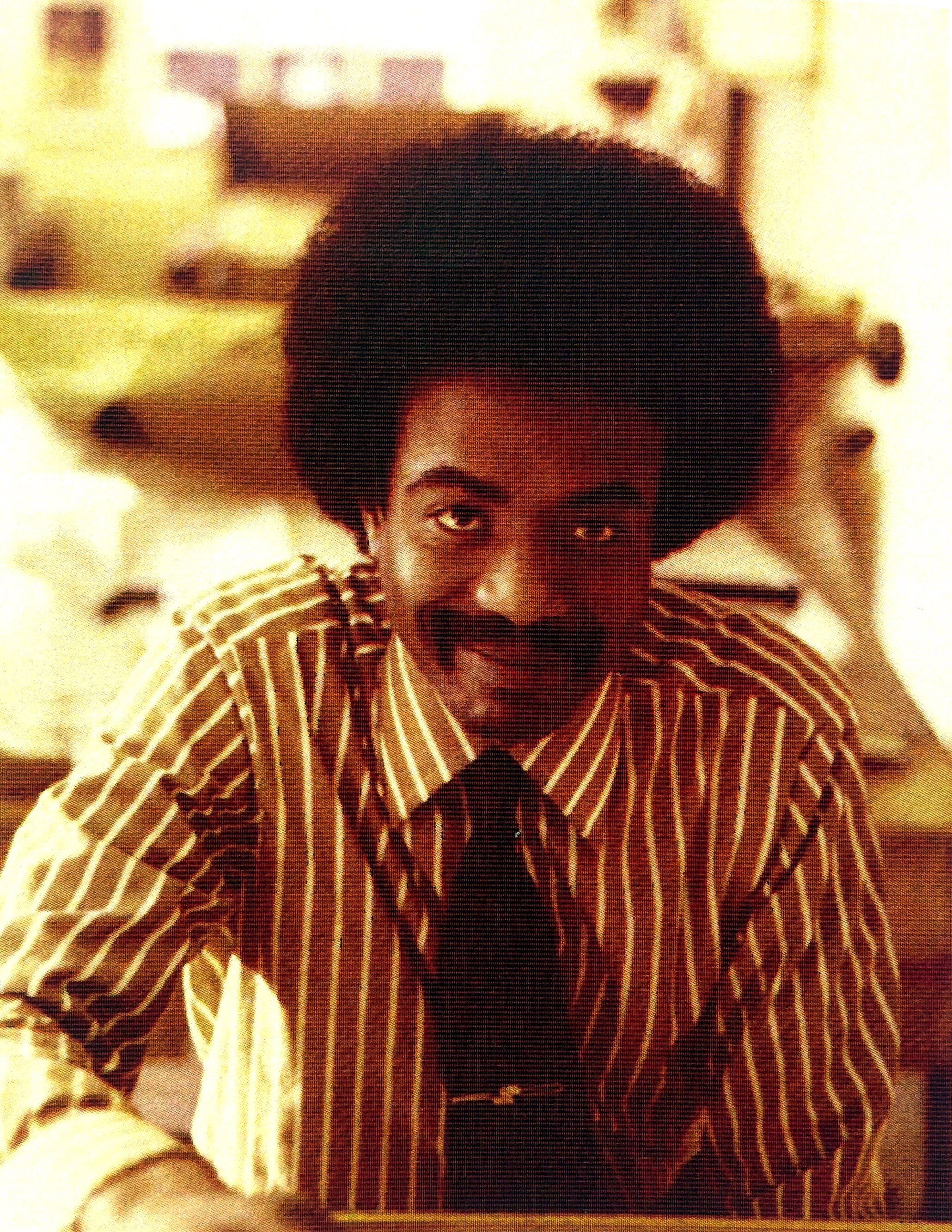

Neville Clare (1946-2015) was diagnosed with sickle cell-haemoglobin C (a variant of sickle cell disease) in 1967. In 1975, frustrated by the lack of knowledge around the condition, he established the Organisation for Sickle Cell Anaemia Research (OSCAR), the first voluntary organization dedicated to sickle cell in the UK. Clare later gained a PhD in health education and was an influential mentor to burgeoning local support groups until his passing in 2015. This image is used with the kind permission of Dr Clare’s family.

BCA DADZIE /4/6. An early leaflet from OSCAR’s first Wood Green branch, spearheaded by Neville Clare. Other branches of OSCAR were subsequently established in Sandwell, Nottingham, Dudley, Bristol, Reading, Croydon and Leicester. Many of these groups still exist, representing the interests of people with SCD to local services and providing a base for support groups. Click to listen to Ajay Dattani of OSCAR Birmingham talking about the organisation’s work.

Sickle cell became a high-profile cause in the 1980s and 1990s. It was championed by celebrities, including television presenter Baroness Floella Benjamin and comedian Sir Lenny Henry, pictured here at Sickle Cell Society events.

Lola Oni is director of the Brent Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia Centre, and previously worked as a health visitor for Lambeth Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia Centre in the 1980s. Click to listen to Lola talk about how patient protest, healthcare workers and celebrity endorsement pushed policymakers to do more for sickle cell.

Laurel Brumant Palmer and Elizabeth Anionwu launching a blood donation campaign. Blood transfusions are an essential treatment for many people with sickle cell disease, and this campaign encouraged more blood donation from Black communities. Click to listen to Laurel talking about first meeting Elizabeth and joining a sickle cell support group as a teenager

Challenging Death in Custody:

The case of Stephen Bogle, as told by Professor Dame Elizabeth Anionwu

Sickle cell voluntary organisations often challenged the British state about its indifference to the health of Black people. These archives deal with the death of Stephen Bogle from a sickle cell crisis in police custody. An inquest eventually found that he died of natural causes aggravated by lack of care. Click to hear Dame Professor Elizabeth Anionwu, the first Sickle Cell Nurse Specialist in the UK and a founding member of the Sickle Cell Society, talk about this case.

BCA 14/05/F. A poster advertising an event about the inadequate treatment of sickle cell in South London in 1990. Copyright Association of Community Health Councils for England and Wales.

An article in 1979 Staunch magazine entitled ‘Sickle cell anaemia: A killer disease’, featuring Neville Clare of OSCAR. Copyright Staunch magazine/Ashton Gibson

Sickle cell became a symbolic condition in the fight for equal treatment for Black British people by the National Health Service. But there was disagreement – some people thought that poor funding for sickle cell illustrated how little the state valued Black health, such as the Liverpool academic and health activist, Ntombenhle Protasia Khotie Torkington. However, others thought it was a rare condition and a distraction from the structural issues that affected more Black Britons’ health, such as poor housing and poverty.

Sickle cell and the myth of ‘race’

Sickle cell was a subject of fascination for Western anthropologists and geneticists in the 1940s and 1950s, because they thought it was a marker of biological ‘race’. However, as Professor Simon Dyson explains in this interview, sickle cell actually demonstrates that biological race is a myth, but that racism is real.

Though it was only after the arrival of the ‘Windrush generation’ that sickle cell was gradually recognized as a condition relevant to British people, sickle cell has been present here for much longer. Click to listen to Lorraine Audley talk about how her grandmother, Mona Sandifer (née Gibson, pictured), who was born in Liverpool in 1925, discovered in her eighties that she had sickle cell disease. Today, approximately 1 in every 500 ‘White British’ babies carries a gene associated with sickle cell.