‘Digging Deep’: The Ipamo Project, 1995-2002

The development project for 107 Tulse Hill was eventually suspended due to projections of increasing costs and high risks identified by an independent evaluation team. Ipamo ceased operational activity in March 1999 when funding from Lambeth Southwark and Lewisham Health Authority (LSL) was withdrawn. After surveying different opportunities, the trustees eventually agreed that the only realistic option was for Ipamo wo be wound down. Remaining funds were given to The Fanon Project, another Lambeth based mental health initiative for African Caribbean communities.

Ipamo was ground-breaking in its vision for autonomous mental health services for Black communities. The theoretical basis of Ipamo, including the ‘Ipamo crisis model’ can still provide a radical framework for mental health services which resist the criminalisation and neglect of Black communities. By acknowledging the impact of environmental stressors in mental health, including the effects race and other social structures have to play in our mental wellbeing, Ipamo’s vision allowed for a a holistic form of mental health treatment which would treat Black communities instead of pathologize. Although Ipamo’s vision for a purpose built treatment facility did not come to fruition, the work of the organisation had a knock on effect in the area, leading to improvements in mental health facilities in Lambeth.

The legacy of Ipamo can be seen in current mental health initiatives in Lambeth such as Black Thrive, which was established in 2016 to address the inequalities that negatively impact the mental health and wellbeing of Black people in Lambeth. The Black Thrive Partnership brings together individuals, local communities, statutory agencies and voluntary organisations to address the structural barriers that prevent Black people from thriving.

https://blackthrive.org/

Closure & Impact

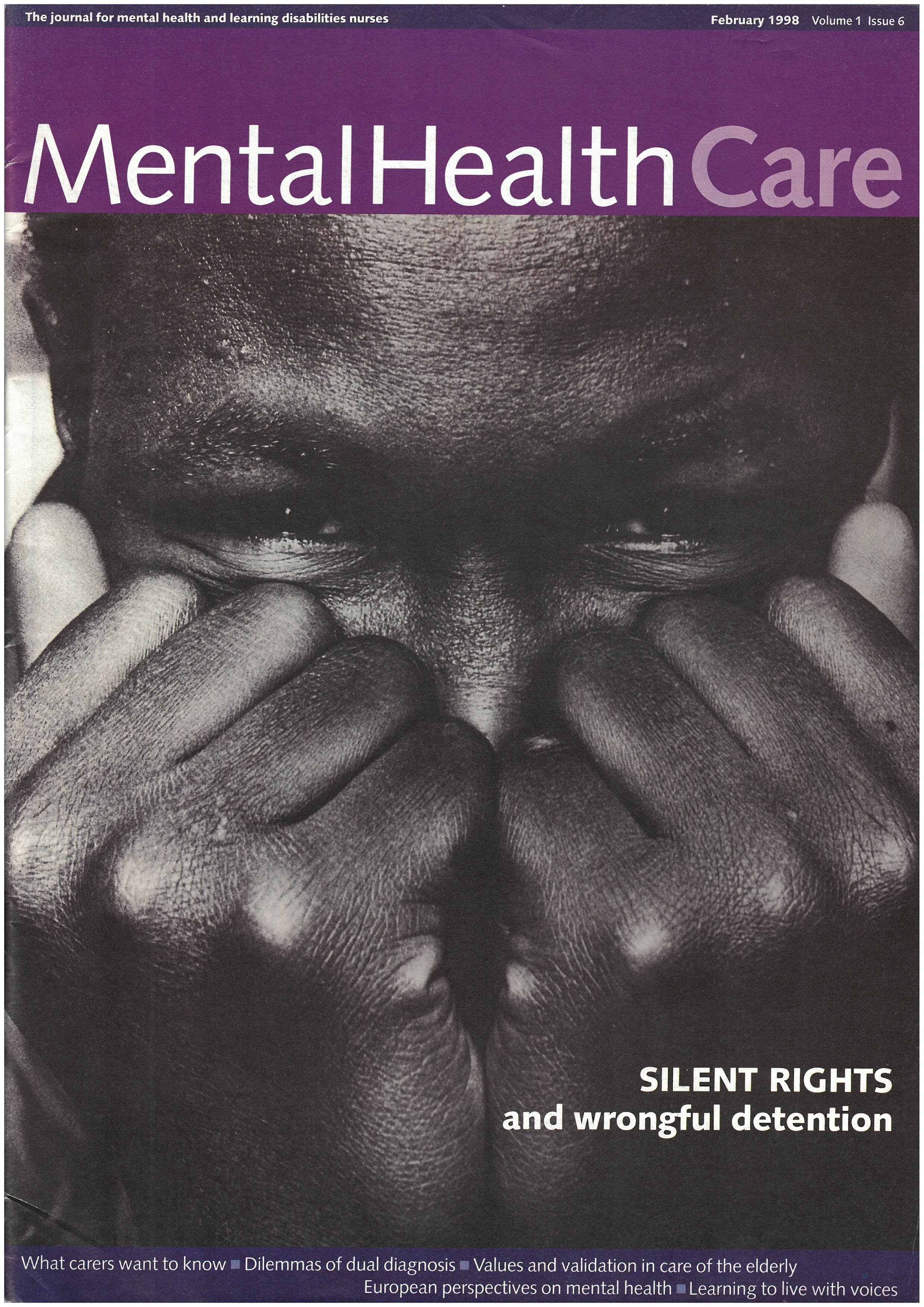

However, there is still work to be done. Inequalities persist within the health system, Black communities still face discrimination and are overrepresented in some of the most coercive state health apparatuses, including forced medication, restraint procedures and institutionalisation. The campaigning of those most impacted by these procedures have led to important changes in the law. One such example is ‘Seni’s Law’ (The Use of Force (Mental Health Units) Bill), which was passed in to reduce the use of force against patients in mental health units. The bill is named after Olaseni Lewis, a man from Croydon in London who died in 2010 aged 23 soon after being restrained by 11 police officers while in a mental health hospital. The Use of Force (Mental Health Units) Bill was passed in 2018 after years of campaigning by his family and a coalition of mental health organisations, practitioners and politicians. The papers of Melba Wilson reflect the decades of campaigning which have taken place in this area, we hope the cataloguing of the papers will inspire new waves of research, and action.